Karnak

Pillars of the Great Hypostyle Hall from the Precinct of Amun-Re | |

| Location | El-Karnak, Luxor Governorate, Egypt |

|---|---|

| Region | Upper Egypt |

| Coordinates | 25°43′6″N 32°39′30″E / 25.71833°N 32.65833°E |

| Type | Sanctuary |

| Part of | Thebes |

| History | |

| Builder | Senusret I–Nectanebo I |

| Material | Stone |

| Founded | c. 1970 BC |

| Periods | Middle Kingdom to Ptolemaic Kingdom |

| Site notes | |

| Condition | Ruin |

| Public access | Yes |

| Official name | Ancient Thebes with its Necropolis |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | I, III, VI |

| Designated | 1979 (3rd session) |

| Reference no. | 87 |

| Region | Arab states |

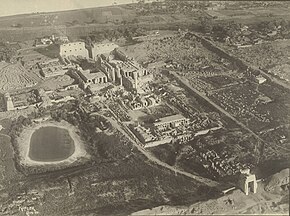

The Karnak Temple Complex, commonly known as Karnak (/ˈkɑːr.næk/),[1] comprises a vast mix of temples, pylons, chapels, and other buildings near Luxor, Egypt. Construction at the complex began during the reign of Senusret I (reigned 1971–1926 BC) in the Middle Kingdom (c. 2000–1700 BC) and continued into the Ptolemaic Kingdom (305–30 BC), although most of the extant buildings date from the New Kingdom. The area around Karnak was the ancient Egyptian Ipet-isut ("The Most Selected of Places") and the main place of worship of the 18th Dynastic Theban Triad, with the god Amun as its head. It is part of the monumental city of Thebes, and in 1979 it was added to the UNESCO World Heritage List along with the rest of the city.[2] Karnak gets its name from the nearby, and partly surrounded, modern village of El-Karnak, 2.5 kilometres (1.6 miles) north of Luxor.

Name

[edit]The original name of the temple was Ipet-isut, meaning "The Most Select of Places".[3] The complex's modern name "Karnak" comes from the nearby village of el-Karnak,[4] which means "fortified village".[5]

Overview

[edit]The complex is a vast open site and includes the Karnak Open Air Museum. It is believed to be the second[citation needed] most visited historical site in Egypt; only the Giza pyramid complex near Cairo receives more visits. It consists of four main parts, of which only the largest is currently open to the public. The term Karnak often is understood as being the Precinct of Amun-Re only, because this is the only part most visitors see. The three other parts, the Precinct of Mut, the Precinct of Montu, and the dismantled Temple of Amenhotep IV, are closed to the public. There also are a few smaller temples and sanctuaries connecting the Precinct of Mut, the Precinct of Amun-Re, and the Luxor Temple. The Precinct of Mut is very ancient, being dedicated to an Earth and creation deity, but not yet restored. The original temple was destroyed and partially restored by Hatshepsut, although another pharaoh built around it in order to change the focus or orientation of the sacred area. Many portions of it may have been carried away for use in other buildings.

The key difference between Karnak and most of the other temples and sites in Egypt is the length of time over which it was developed and used. Construction of temples started in the Middle Kingdom and continued into Ptolemaic times. Approximately thirty pharaohs contributed to the buildings, enabling it to reach a size, complexity, and diversity not seen elsewhere. Few of the individual features of Karnak are unique, but the size and number of features are vast. The deities represented range from some of the earliest worshipped to those worshipped much later in the history of the Ancient Egyptian culture. Although destroyed, it also contained an early temple built by Amenhotep IV (Akhenaten), the pharaoh who later would celebrate a nearly monotheistic religion he established that prompted him to move his court and religious center away from Thebes. It also contains evidence of adaptations, where the buildings of the ancient Egyptians were used by later cultures for their own religious purposes, such as Coptic churches.

Hypostyle Hall

[edit]

The Great Hypostyle Hall in the Precinct of Amun-Re has an area of 50,000 sq ft (5,000 m2) with 134 massive columns arranged in 16 rows. One hundred and twenty-two of these columns are 10 metres (33 ft) tall, and the other 12 are 21 metres (69 ft) tall with a diameter of over 3 metres (9.8 ft). The architraves, on top of these columns, are estimated to weigh 70 tons.

These architraves may have been lifted to these heights using levers. This would be a time-consuming process and also would require great balance to get to such heights. A common alternative theory regarding how they were moved is that large ramps were constructed of sand, mud, brick or stone and that the stones were then towed up the ramps. If stone had been used for the ramps, they would have been able to use much less material. The top of the ramps presumably would have employed either wooden tracks or cobblestones for towing the megaliths.

There is an unfinished pillar in an out-of-the-way location that indicates how it would have been finished. Final carving was executed after the drums were put in place so that it was not damaged while being placed.[6][7] Several experiments moving megaliths with ancient technology were made at other locations – some of which are amongst the largest monoliths in the world.

The sun god's shrine was built so that it has light focused upon it during the winter solstice.[8]

In 2009, UCLA launched a website dedicated to virtual reality digital reconstructions of the Karnak complex and other resources.[9]

History

[edit]

The history of the Karnak complex is largely the history of Thebes and its changing role in the culture. Religious centers varied by region, and when a new capital of the unified culture was established, the religious centers in that area gained prominence. The city of Thebes does not appear to have been of great significance before the Eleventh Dynasty and previous temple building there would have been relatively small, with shrines being dedicated to the early deities of Thebes, the Earth goddess Mut and Montu. Early building was destroyed by invaders. The earliest known artifact found in the area of the temple is a small, eight-sided column from the Eleventh Dynasty, which mentions Amun-Re. Amun (sometimes called Amen) was long the local tutelary deity of Thebes. He was identified with the ram and the goose. The Egyptian meaning of Amun is "hidden" or the "hidden god".[10]

Major construction work in the Precinct of Amun-Re took place during the Eighteenth Dynasty, when Thebes became the capital of the unified Ancient Egypt. Almost every pharaoh of that dynasty added something to the temple site. Thutmose I erected an enclosure wall connecting the Fourth and Fifth pylons, which comprise the earliest part of the temple still standing in situ. Hatshepsut had monuments constructed and also restored the original Precinct of Mut, that had been ravaged by the foreign rulers during the Hyksos occupation. She had twin obelisks, at the time the tallest in the world, erected at the entrance to the temple. One still stands, as the second-tallest ancient obelisk still standing on Earth; the other has toppled and is broken.

Another of her projects at the site, Karnak's Red Chapel or Chapelle Rouge, was intended as a barque shrine and originally may have stood between her two obelisks. She later ordered the construction of two more obelisks to celebrate her sixteenth year as pharaoh; one of the obelisks broke during construction, and thus, a third was constructed to replace it. The broken obelisk was left at its quarrying site in Aswan, where it still remains. Known as the unfinished obelisk, it provides evidence of how obelisks were quarried.[11]

Construction of the Great Hypostyle Hall also may have begun during the Eighteenth Dynasty (although most new building was undertaken under Seti I and Ramesses II in the Nineteenth). Merneptah, also of the Nineteenth Dynasty, commemorated his victories over the Sea Peoples on the walls of the Cachette Court, the start of the processional route (also known as the Avenue of Sphinxes) to the Luxor Temple. The last major change to the Precinct of Amun-Re's layout was the addition of the First Pylon and the massive enclosure walls that surround the precinct, both constructed by Nectanebo I of the Thirtieth Dynasty.

Ancient Greek and Roman writers wrote about a range of monuments in Upper Egypt and Nubia, including Karnak, Luxor temple, the Colossi of Memnon, Esna, Edfu, Kom Ombo, Philae, and others.

In 323 AD, Roman emperor Constantine the Great recognized the Christian religion, and in 356 Constantius II ordered the closing of pagan temples throughout the Roman empire, into which Egypt had been annexed in 30 BC. Karnak was by this time mostly abandoned, and Christian churches were founded among the ruins, the most famous example of this is the reuse of the Festival Hall of Thutmose III's central hall, where painted decorations of saints and Coptic inscriptions can still be seen.

European knowledge of Karnak

[edit]Thebes' exact placement was unknown in medieval Europe, though both Herodotus and Strabo give the exact location of Thebes and how long up the Nile one must travel to reach it. Maps of Egypt, based on the 2nd century Claudius Ptolemaeus' mammoth work Geographia, had been circulating in Europe since the late 14th century, all of them showing Thebes' (Diospolis) location. Despite this, several European authors of the 15th and 16th centuries who visited only Lower Egypt and published their travel accounts, such as Joos van Ghistele and André Thévet, put Thebes in or close to Memphis.

The first European description of the Karnak temple complex was by unknown Venetian in 1589 and is housed in the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze, although his account gives no name for the complex.

Karnak ("Carnac") as a village name, and name of the complex, is first attested in 1668, when two capuchin missionary brothers, Protais and Charles François d'Orléans, travelled though the area. Protais' writing about their travel was published by Melchisédech Thévenot (Relations de divers voyages curieux, 1670s–1696 editions) and Johann Michael Vansleb (The Present State of Egypt, 1678).

The first drawing of Karnak is found in Paul Lucas' travel account of 1704, (Voyage du Sieur Paul Lucas au Levant). It is rather inaccurate, and can be quite confusing to modern eyes. Lucas travelled in Egypt during 1699–1703. The drawing shows a mixture of the Precinct of Amun-Re and the Precinct of Montu, based on a complex confined by the three huge Ptolemaic gateways of Ptolemy III Euergetes / Ptolemy IV Philopator, and the massive 113 m long, 43 m high and 15 m thick, First Pylon of the Precinct of Amun-Re.

Karnak was visited and described in succession by Claude Sicard and his travel companion Pierre Laurent Pincia (1718 and 1720–21), Granger (1731), Frederick Louis Norden (1737–38), Richard Pococke (1738), James Bruce (1769), Charles-Nicolas-Sigisbert Sonnini de Manoncourt (1777), William George Browne (1792–93), and finally by a number of scientists of the Napoleon expedition, including Vivant Denon, during 1798–1799. Claude-Étienne Savary describes the complex in rather great detail in his work of 1785; especially in light of the fact that it is a fictional account of a pretend journey to Upper Egypt, composed out of information from other travellers. Savary did visit Lower Egypt in 1777–78, and published a work about that too.

Main parts

[edit]

Precinct of Amun-Re

[edit]This is the largest of the precincts of the temple complex, and is dedicated to Amun-Re, the chief deity of the Theban Triad. There are several colossal statues, including the figure of Pinedjem I which is 10.5 metres (34 ft) tall. The sandstone for this temple, including all of the columns, was transported from Gebel Silsila 100 miles (161 km) south on the Nile river.[12] It also has one of the largest obelisks, weighing 328 tons and standing 29 metres (95 ft) tall.[13][14]

Precinct of Mut

[edit]

Located to the south of the newer Amun-Re complex, this precinct was dedicated to the mother goddess, Mut, who became identified as the wife of Amun-Re in the Eighteenth Dynasty Theban Triad. It has several smaller temples associated with it and has its own sacred lake, constructed in a crescent shape. This temple has been ravaged, many portions having been used in other structures. Following excavation and restoration works by the Johns Hopkins University team, led by Betsy Bryan (see below) the Precinct of Mut has been opened to the public. Six hundred black granite statues were found in the courtyard to her temple. It may be the oldest portion of the site.

In 2006, Bryan presented her findings of a festival that included apparent intentional overindulgence in alcohol.[15] Participation in the festival included the priestesses and the population. Historical records of tens of thousands attending the festival exist. These findings were made in the temple of Mut because when Thebes rose to greater prominence, Mut absorbed the warrior goddesses, Sekhmet and Bast, as some of her aspects. First, Mut became Mut-Wadjet-Bast, then Mut-Sekhmet-Bast (Wadjet having merged into Bast), then Mut also assimilated Menhit, another lioness goddess, and her adopted son's wife, becoming Mut-Sekhmet-Bast-Menhit, and finally becoming Mut-Nekhbet.

Temple excavations at Luxor discovered a "porch of drunkenness" built onto the temple by the pharaoh Hatshepsut, during the height of her twenty-year reign. In a later myth developed around the annual drunken Sekhmet festival, Ra, by then the sun god of Upper Egypt, created her from a fiery eye gained from his mother, to destroy mortals who conspired against him (Lower Egypt). In the myth, Sekhmet's blood-lust was not quelled at the end of the battle and led to her destroying almost all of humanity, so Ra had tricked her by turning the Nile as red as blood (the Nile turns red every year when filled with silt during inundation) so that Sekhmet would drink it. The trick, however, was that the red liquid was not blood, but beer mixed with pomegranate juice so that it resembled blood, making her so drunk that she gave up slaughter and became an aspect of the gentle Hathor. The complex interweaving of deities occurred over the thousands of years of the culture.

Precinct of Montu

[edit]This portion of the site is dedicated to the son of Mut and Amun-Re, Montu, a war-god. It is located to the north of the Amun-Re complex and is much smaller in size. It is not open to the public.

Temple of Amenhotep IV (deliberately dismantled)

[edit]The temple that Akhenaten (Amenhotep IV) constructed on the site was located east of the main complex, outside the walls of the Amun-Re precinct. It was destroyed immediately after the death of its builder, who had attempted to overcome the powerful priesthood who had gained control over Egypt before his reign. It was so thoroughly demolished that its full extent and layout is unknown. The priesthood of that temple regained their powerful position as soon as Akhenaten died, and were instrumental in destroying many records of his existence.

Gallery

[edit]-

Luxor dromos, an avenue of human-headed sphinxes which once connected the temples of Karnak and Luxor.

-

The Sacred Lake of the Precinct of Amun-Re

-

View of the first pylon of the temple of Amun-Re at Karnak

-

Ram-headed sphinx statues at Karnak

-

Hypostyle hall of the Precinct of Amun-Re, as it appeared in 1838 in The Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt, and Nubia

-

Colossal statue of Ramses II

-

Open papyrus umbel capitals of the Hypostyle Hall

-

Closed papyrus umbel capitals of the Hypostyle Hall

-

Karnak Temple pillar up-close

-

Obelisk of Thutmosis I in Karnak

-

Statue of Khepri in Karnak

-

Karnak, Egypt; Gate and Pylon., n.d., Brooklyn Museum Archives

-

Karnak, Egypt; Great Statues., n.d., Goodyear. Brooklyn Museum Archives

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Karnak". Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Dictionary, Eleventh Edition. Merriam-Webster, 2007. p. 1550

- ^ "Ancient Thebes with its Necropolis". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ^ Wilkinson, Richard H. (2000). The Complete Temples of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson. p. 154. ISBN 978-0-500-05100-9. Retrieved 21 March 2024.

- ^ Wilkinson, Richard H. (2000). The Complete Temples of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson. p. 154. ISBN 978-0-500-05100-9.

- ^ Peust, Carsten (2010). Die Toponyme Vorarabischen Ursprungs im Modernen Ägypten: Ein Katalog (Göttinger Miszellen Beihefte Nr. 8) (PDF) (in German). Göttingen: Universität Göttingen. p. 56. Retrieved 21 March 2024.

- ^ Egypt: Engineering an empire engineering feats

- ^ Lehner, Mark The Complete Pyramids, London: Thames and Hudson (1997) pp.202–225 ISBN 0-500-05084-8.

- ^ "Everything You Need to Know About the Winter Solstice". National Geographic. 21 December 2015. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- ^ "Ancient Egypt Brought To Life With Virtual Model Of Historic Temple Complex", Science Daily, 30 April 2009, retrieved 12 June 2009 [1]

- ^ Stewert, Desmond and editors of the Newsweek Book Division "The Pyramids and Sphinx" 1971 pp. 60–62

- ^ The Unfinished Obelisk by Peter Tyson 16 March 1999 NOVA online adventure

- ^ Time Life Lost Civilizations series: Ramses II: Magnificence on the Nile (1993) pp. 53–54

- ^ Walker, Charles, 1980 "Wonders of the Ancient World" pp24–7

- ^ "The Seventy Wonders of the Ancient World", edited by Chris Scarre (1999) Thames & Hudson, London

- ^ "Sex and booze figured in Egyptian rites" nbcnews.com, 30 October 2006,

Further reading

[edit]- Blyth, Elizabeth (2006). Karnak: Evolution of a Temple. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-96837-6.

External links

[edit]- CFEETK – Centre Franco-Égyptien d'Étude des Temples de Karnak (en)

- Temple of Amun, numerous photos & schemes (comments in russian)

- Karnak images

- www.karnak3d.net :: "Web-book" The 3D reconstruction of the Great Temple of Amun in Karnak. Marc

- Digital Karnak UCLA

- Karnak Temple picture gallery at Remains.se