Goose Gossage

| Goose Gossage | |

|---|---|

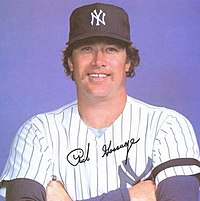

Gossage in 2007 | |

| Pitcher | |

| Born: July 5, 1951 Colorado Springs, Colorado, U.S. | |

Batted: Right Threw: Right | |

| Professional debut | |

| MLB: April 16, 1972, for the Chicago White Sox | |

| NPB: July 4, 1990, for the Fukuoka Daiei Hawks | |

| Last appearance | |

| NPB: October 10, 1990, for the Fukuoka Daiei Hawks | |

| MLB: August 8, 1994, for the Seattle Mariners | |

| MLB statistics | |

| Win–loss record | 124–107 |

| Earned run average | 3.01 |

| Strikeouts | 1,502 |

| Saves | 310 |

| NPB statistics | |

| Win–loss record | 2–3 |

| Earned run average | 4.40 |

| Strikeouts | 40 |

| Saves | 8 |

| Stats at Baseball Reference | |

| Teams | |

| Career highlights and awards | |

| |

| Member of the National | |

| Induction | 2008 |

| Vote | 85.8% (ninth ballot) |

Richard Michael "Goose" Gossage (born July 5, 1951) is an American former baseball pitcher who played 22 seasons in Major League Baseball (MLB) between 1972 and 1994. He pitched for nine different teams, spending his best years with the New York Yankees and San Diego Padres.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Gossage was one of the earliest manifestations of the modern closer, with a bold mustache and a gruff demeanor to go along with his overpowering 100 mph fastball.[1] He led the American League (AL) in saves three times and was runner-up twice; by the end of the 1987 season he ranked second in major-league career saves, trailing only Rollie Fingers, although by the end of his career his total of 310 had slipped to fourth all time. When he retired he also ranked third in major-league career games pitched (1,002), and he remains third in wins in relief (115) and innings pitched in relief (1,5562⁄3); his 1,502 strikeouts place him behind only Hoyt Wilhelm among pitchers who pitched primarily in relief. He also is the career leader in blown saves (112). From 1977 through 1983 he never recorded an earned run average over 2.62, including a mark of 0.77 in 1981, and in 1980 he finished third in AL voting for both the MVP Award and Cy Young Award as the Yankees won a division title.[2]

Respected for his impact in crucial games, Gossage recorded the final out to clinch a division, league, or World Series title seven times. His eight All-Star selections as a reliever were a record until Mariano Rivera passed him in 2008; he was also selected once as a starting pitcher. In 2008, Gossage was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame. He now works in broadcasting.

Early life

[edit]Richard Michael "Goose" Gossage was born on July 5, 1951, in Colorado Springs, Colorado, and he grew up near N. Cascade Avenue. He graduated in 1970 from Wasson High School, where he played on the baseball and basketball teams and is included in the school's athletic "Wall of Fame".[3] His wife Corna Gossage also graduated from Wasson High.

Professional career

[edit]Draft and minor leagues

[edit]The Chicago White Sox selected him in the ninth round of the 1970 Major League Baseball draft.

Chicago White Sox (1972–1976)

[edit]Gossage led the American League (AL) in saves in 1975 (26).

Pittsburgh Pirates (1977)

[edit]After the 1976 season, the White Sox traded Gossage and Terry Forster to the Pittsburgh Pirates for Silvio Martinez and Richie Zisk.[4]

New York Yankees (1978–1983)

[edit]Gossage became a free agent after the 1977 season, and signed with the New York Yankees for $3.6 million over six years.[5]

Gossage again led the AL in saves in 1978 (27) and 1980 (33). On October 2, 1978, he earned the save in the Yankees' one-game playoff against the Boston Red Sox for the AL East title, entering with one out in the seventh inning and a 4–2 lead following Bucky Dent's home run; although he allowed two runs in the eighth inning, he held on to preserve the 5–4 victory, getting Carl Yastrzemski to pop up to third baseman Graig Nettles with two out and two men on base in the ninth inning to clinch the division championship. He was also on the mound five days later when the Yankees clinched the pennant in the ALCS against the Kansas City Royals, entering Game 4 in the ninth inning with a 2–1 lead and a runner on second base; he earned the save by striking out Clint Hurdle and retiring Darrell Porter and Pete LaCock on fly balls. He was on the mound ten days later when they captured the World Series title against the Los Angeles Dodgers for their second consecutive championship, coming on with no one out in the eighth inning of Game 6; he retired Ron Cey on a popup to catcher Thurman Munson to clinch the win.

On April 19, 1979, following a Yankee loss to the Baltimore Orioles, Reggie Jackson started kidding Cliff Johnson about his inability to hit Gossage. While Johnson was showering, Gossage insisted to Jackson that he struck out Johnson all the time when he used to face him, and that he was terrible at the plate. “He either homers or strikes out”, Gossage said. He had previously given Johnson the nickname “Breeze” in reference to how his big swing kept Gossage cool on the pitcher’s mound in hot weather. When Jackson relayed this information to Johnson upon his return to the locker room, all the players assembled, egged on by Jackson, started laughing at him and in unison loudly called him “Breeze” with some waving their arms and hands before doubling over. This infuriated Johnson and a fight started between him and Gossage. Gossage tore ligaments in his right thumb and missed three months of the season which cost the Yankees a chance to win their third consecutive World Series title. Yankees owner George Steinbrenner was furious and fined both Johnson and Gossage. Teammate Tommy John called it "a demoralizing blow to the team."[6] Johnson was traded to Cleveland two months after the brawl.[7] Ron Guidry, the reigning Cy Young Award winner, volunteered to go to the bullpen to replace him. In the first game of a doubleheader on October 4, 1980, Gossage pitched the last two innings of a 5–2 win over the Detroit Tigers, earning his career-high 33rd save as New York clinched another division title. On October 10, George Brett of the Royals hit a tide-turning three-run homer off Gossage into Yankee Stadium's right-field upper deck to lead the Royals to a three-game sweep in the AL Championship Series, after the Yankees had defeated the Royals in three consecutive ALCS from 1976 to 1978. Almost three years later during the regular season, Brett got to Gossage again in the Bronx, blasting a go-ahead two-run home run in the top of the ninth in a game memorialized as the "Pine Tar Game".

Gossage recorded saves in all three Yankee victories in the 1981 AL Division Series against the Milwaukee Brewers, not allowing a run in 6+2⁄3 innings, and he was again the final pitcher when they clinched the 1981 pennant against the Oakland Athletics. In 1983, his last season with the Yankees, Gossage broke Sparky Lyle's club record of 141 career saves; Dave Righetti passed his final total of 150 in 1988. Gossage holds the Yankees' career record for ERA (2.14) and hits per nine innings (6.59) among pitchers with at least 500 innings for the team.

In eight of his first ten seasons as a closer, Gossage's ERA was less than 2.27.[8] Over his career, right-handed hitters hit .211 against him.

Gossage became upset with Yankees' owner George Steinbrenner for meddling with the team. In 1982, he called Steinbrenner "the fat man upstairs", and disapproved of the way Yankees' manager Billy Martin used him. Gossage became a free agent after the 1983 season, and insisted that he would not re-sign with New York.[9]

San Diego Padres (1984–1987)

[edit]Gossage signed with the San Diego Padres. In 1984, Gossage clinched another title, earning the save in Game 5 of the NL Championship Series and sending the Padres to their first World Series; after San Diego had scored four runs in the seventh inning to take a 6–3 lead against the Chicago Cubs, Gossage pitched the final two innings, getting Jody Davis to hit into a force play for the final out. During Game 5 of the 1984 World Series versus the Detroit Tigers, after receiving signs from the coaches on the Padres bench and a mound visit by manager Dick Williams, Gossage refused to intentionally walk right fielder Kirk Gibson with two runners on and first base open. On the second pitch, Gossage and the Padres would regret that decision as Gibson homered to deep right field, clinching a World Series win for the Tigers. On August 17, 1986, Gossage struck out Pete Rose in Rose's final Major League at bat.[10]

Chicago Cubs (1988)

[edit]Gossage was dealt along with Ray Hayward from the Padres to the Cubs for Keith Moreland and Mike Brumley on February 12, 1988.[11] On August 6, 1988, while with the Cubs, Gossage became the second pitcher to record 300 career saves in a 7–4 victory over the Philadelphia Phillies, coming into the game with two out in the ninth and two men on base and retiring Phil Bradley on a popup to second baseman Ryne Sandberg. He was released by the Cubs in March 1989.[12]

San Francisco Giants (1989)

[edit]Gossage signed with the San Francisco Giants in April.[13]

New York Yankees (1989)

[edit]The Yankees selected Gossage off of waivers in August.[14]

Fukuoka Daiei Hawks (1990)

[edit]Gossage pitched for the Fukuoka Daiei Hawks of Nippon Professional Baseball in 1990.

Texas Rangers (1991)

[edit]Gossage signed with the Texas Rangers for the 1991 season.

Oakland Athletics (1992–1993)

[edit]Gossage signed one-year contracts to pitch for the Oakland Athletics in 1992 and 1993.[13]

Seattle Mariners (1994)

[edit]

Gossage signed with the Seattle Mariners for the 1994 season. On August 4, 1994, Gossage became the third pitcher in major league history to appear in 1,000 games. Gossage entered a game against the California Angels with two out in the seventh inning and runners on second and third base, trailing 2–1; he picked up the win when the Mariners scored three times in the eighth for a 4–2 victory. In his final major league appearance on August 8, he earned a save of three innings—his first in over 15 months—in the Mariners' 14–4 win over the Rangers, retiring all nine batters he faced; José Canseco flied out to left field to end the game.

Gossage had a record 112 career blown saves. ESPN.com noted that blown saves are "non-qualitative", pointing out that the two career leaders—Gossage and Rollie Fingers (109)—were both inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame.[15] Fran Zimniuch in Fireman: The Evolution of the Closer in Baseball wrote, "But you have to be a great relief pitcher to blow that many saves. Clearly, [Gossage] saved many, many more than he did not save."[16] More than half of Gossage's blown saves came in tough situations, with the tying run on base when the pitcher entered. In nearly half of those blown tough saves, he entered the game in the sixth or seventh inning. Multiple-inning outings provide more chances for a reliever to blow a save, as he needs not only to get out of the initial situation but also to pitch additional innings in which to possibly lose the lead.[17]

Pioneer of the closer role

[edit]The New York Yankees of the late 1970s and early 1980s arguably pioneered the set-up/closer configuration, which was a standard baseball practice until the 2010s. The most effective pairing was Ron Davis and Gossage, with Davis typically entering the game in the 7th or 8th innings and Gossage finishing up. During one stretch with that pairing, the Yankees won 77 of 79 games in which they led after six innings.[citation needed]

Gossage and top relievers of his era were known as firemen, relievers who entered the game when a lead was in jeopardy—usually with men on base—and regardless of the inning and often pitching two or three innings while finishing the game.[18][19][20] Gossage had 17 games where he recorded at least 10 outs in his first season as a closer, including three games where he went seven innings. He pitched over 130 innings as a reliever in three different seasons.[19] He had more saves of at least two innings than saves where he pitched one inning or less.[21] The ace reliever's role evolved into that of a closer, whose use was reserved for games where the team had a lead of three runs or less in the ninth inning.[22] Mariano Rivera, considered the greatest closer of all time,[23] earned only one save of seven-plus outs in his career, while Gossage logged 53.[24] "Don't tell me [Rivera's] the best relief pitcher of all-time until he can do the same job I did. He may be the best modern closer, but you have to compare apples to apples. Do what we did," said Gossage.[25]

During his career, Gossage pitched in 1,002 games and finished 681 of them, earning 310 saves. Per nine innings pitched, he averaged 7.45 hits allowed and 7.47 strikeouts. He also made nine All-Star appearances and pitched in three World Series.

Pitching style

[edit]Gossage was one of the few pitchers who employed basically just one pitch, a rising 100 mph fastball.[1]. Occasionally he would throw a slurve or a changeup. Despite his reputation as a pitcher who threw high and tight to brush batters back, Gossage stated that he intentionally threw at only three hitters in his career: Ron Gant, Andrés Galarraga, and Al Bumbry.[26]

Nickname

[edit]The nickname "Goose" came about when a friend did not like Gossage's nickname "Goss", and noted he looked like a goose when he extended his neck to see the signs given by the catcher.[27][28] Although Gossage is otherwise generally referred to as "Rich" in popular media, a youth sports complex in his hometown of Colorado Springs named after him bears the name "Rick", displaying "Rick 'Goose' Gossage Youth Sports Complex".[29]

Retirement

[edit]

Gossage lives in his home town, Colorado Springs, Colorado, and is active in the community promoting and sponsoring youth sports. In 1995, the city of Colorado Springs dedicated the Rick "Goose" Gossage Youth Sports Complex,[30] which features five fields for youth baseball and softball competition. He also owned hamburger restaurants in Greeley and Parker, Colorado, called Burgers N Sports.

He has written an autobiography, released in 2000, entitled The Goose is Loose (Ballantine: New York).

His son, Todd, is a professional baseball player who has played for the Sussex Skyhawks, Newark Bears, and Rockland Boulders of the Can-Am League.

Gossage coached the American League team in the Taco Bell All-Star Legends & Celebrity Softball Game in Anaheim, California on July 12, 2010.[31]

At the Hall of Fame induction in 2008, Gossage expressed gratitude to a number of baseball people who had helped him through his career, and several times described his Hall of Fame week experience as "amazing".[32] The inductions included Dick Williams, his manager at San Diego. After the ceremonies, the two of them sat together for an ESPN interview on the podium, taking audience questions and gently ribbing each other, especially about the upper-deck home run Kirk Gibson hit off Gossage in Game 5 of the 1984 World Series.

The Yankees honored Gossage with a plaque in Monument Park on June 22, 2014.[33]

In his retirement Gossage has expressed support of former US President Donald J. Trump and an equal disdain for Trump's opponents. He has also openly criticized the Black Lives Matter movement and organization as well.[34] Due to these comments and continuous criticism of New York Yankees players (especially Mariano Rivera), and front office executives such as Brian Cashman and Hal Steinbrenner, Gossage has been disinvited from Yankees Spring Training and other events such as "Old Timers' Day."[35]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Goose Gossage, National Baseball Hall of Fame

- ^ "Chat: Chat with former pitcher Goose Gossage – SportsNation". ESPN. Archived from the original on July 29, 2013. Retrieved April 14, 2014.

- ^ "Ramsey: Gossage looks back at Wasson memories". June 2013.

- ^ "Sarasota Herald-Tribune - Google News Archive Search". news.google.com.

- ^ Chass, Murray (November 23, 1977). "Yanks Sign Gossage To $3.6 Million Pact". The New York Times – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ John, Tommy; Valenti, Dan (1991). TJ: My Twenty-Six Years in Baseball. New York: Bantam. p. 201. ISBN 0-553-07184-X.

- ^ "Cliff Johnson traded". Milwaukee Journal. Associated Press. June 16, 1979. Archived from the original on April 23, 2020. Retrieved October 18, 2011.

- ^ "Famers on the Fringe". ESPN.com. December 20, 2006. Retrieved August 1, 2008.

- ^ "Gainesville Sun - Google News Archive Search". news.google.com.

- ^ Baseball's Top 100: The Game's Greatest Records, p. 11, Kerry Banks, 2010, Greystone Books, Vancouver, BC, ISBN 978-1-55365-507-7

- ^ Mitchell, Fred (February 13, 1988). "Cubs Deal Moreland For Gossage – Chicago Tribune". Articles.chicagotribune.com. Retrieved April 14, 2014.

- ^ "The feared fastball is gone, and so is 'Goose' Gossage". The Daily News. AP. March 29, 1989. Retrieved December 27, 2014.

- ^ a b Alfonso L.; Tusa C. (October 27, 2011). "Rich Gossage-SABR". SABR Baseball Biography Project. Society for American Baseball Research. Retrieved December 27, 2014.

After one year in Chicago, "experimenting with off-speed pitches to compensate for a diminished fastball," he was released. The 1989 season featured a stop with the San Francisco Giants and a brief return to the Yankees.

- ^ "Gossage Rejoins Yanks". The New York Times. The Associated Press. August 11, 1989. Retrieved May 17, 2024 – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ Philip, Tom (April 30, 2011). "Blown saves are overblown". ESPN.com. Archived from the original on August 8, 2011.

- ^ Zimniuch, Fran (2010). Fireman: The Evolution of the Closer in Baseball. Chicago: Triumph Books. p. 98. ISBN 978-1-60078-312-8.

- ^ Schechter, Gabriel (March 21, 2006). "Top Relievers in Trouble". National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Archived from the original on June 8, 2007.

- ^ Jenkins, Chris (September 25, 2006). "Where's the fire?". The San Diego Union-Tribune. Archived from the original on June 28, 2011.

- ^ a b Caple, Jim (August 5, 2008). "The most overrated position in sports". ESPN.com. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved March 23, 2017.

- ^ Zimniuch 2010, pp.xx,81

- ^ Schecter, Gabriel (January 18, 2006). "The Evolution of the Closer". National Baseball Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on June 8, 2007.

Sutter and Gossage had more saves where they logged at least two innings than saves where they pitched an inning or less.

- ^ Baseball Prospectus Team of Experts (2007). Baseball Between the Numbers: Why Everything You Know About the Game Is Wrong. New York: Basic Books. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-465-00547-5. Retrieved February 23, 2011.

- ^ Red, Christian (March 13, 2010). "Modern Yankee Heroes: From humble beginnings, Mariano Rivera becomes the greatest closer in MLB history". Daily News. Archived from the original on March 10, 2012. Retrieved December 2, 2011.

- ^ Rosen, Charlie (2011). Bullpen Diaries: Mariano Rivera, Bronx Dreams, Pinstripe Legends, and the Future of the New York Yankees. HarperCollins Publishers. p. 213. ISBN 978-0-06-200598-4.

- ^ Zimniuch 2010, p. 97

- ^ "The Official Site of The New York Yankees: News: Goose not a fan of Joba's celebrations". MLB.com. Retrieved September 4, 2008.

- ^ Kaplan, Jim (September 29, 1980). "He's The Golden Goose". Sports Illustrated. New York, NY: Time Inc.

- ^ Bradley, Richard (2008). The Greatest Game. New York, NY: Free Press. pp. 74–75. ISBN 978-1-4165-3439-6 – via Google Books.

- ^ Goldsmith, Tamera. "Photo, Sign, Gossage Youth Sports Complex". Photobucket. Seattle, WA: Photobucket Corporation. Retrieved May 2, 2021.

- ^ "07082009.jpg Photo by TameraGoldsmith | Photobucket". Media.photobucket.com. Retrieved April 14, 2014.

- ^ "Photos: MLB stars and celebrities at play at Angels Stadium - Las Vegas Sun Newspaper". www.lasvegassun.com.

- ^ "'Storybook career' leads Goose to Hall | MLB.com: News". Mlb.mlb.com. March 27, 2014. Retrieved April 14, 2014.

- ^ "Yankees to honor Joe Torre, Rich "Goose" Gossage, Tino Martinez, and Paul O'Neill in 2014 with plaques in Monument Park; Torre's uniform no. 6 to also be retired: Ceremonies are part of a recognition series that will include Bernie Williams in 2015" (Press release). MLB.com. May 8, 2014. Retrieved September 12, 2024.

- ^ "Yankees' Goose Gossage defends Curt Schilling, Donald Trump in revealing Q & A". January 29, 2021.

- ^ "Yankees great Goose Gossage prays bleeping liberals 'go off the cliff' for attacking President Trump in epic rant". April 15, 2020.

External links

[edit]- Goose Gossage at the Baseball Hall of Fame

- Career statistics from MLB, or ESPN, or Baseball Reference, or Fangraphs, or Baseball Reference (Minors), or Retrosheet

- Goose Gossage at the SABR Baseball Biography Project

- Official website

- 1951 births

- Living people

- National Baseball Hall of Fame inductees

- Major League Baseball pitchers

- Chicago Cubs players

- Chicago White Sox players

- New York Yankees players

- Oakland Athletics players

- Pittsburgh Pirates players

- San Diego Padres players

- San Francisco Giants players

- Seattle Mariners players

- Texas Rangers players

- American League All-Stars

- National League All-Stars

- American League saves champions

- American expatriate baseball players in Japan

- Fukuoka Daiei Hawks players

- Baseball players from Colorado Springs, Colorado

- Gulf Coast White Sox players

- Appleton Foxes players

- Iowa Oaks players

- Oklahoma City 89ers players